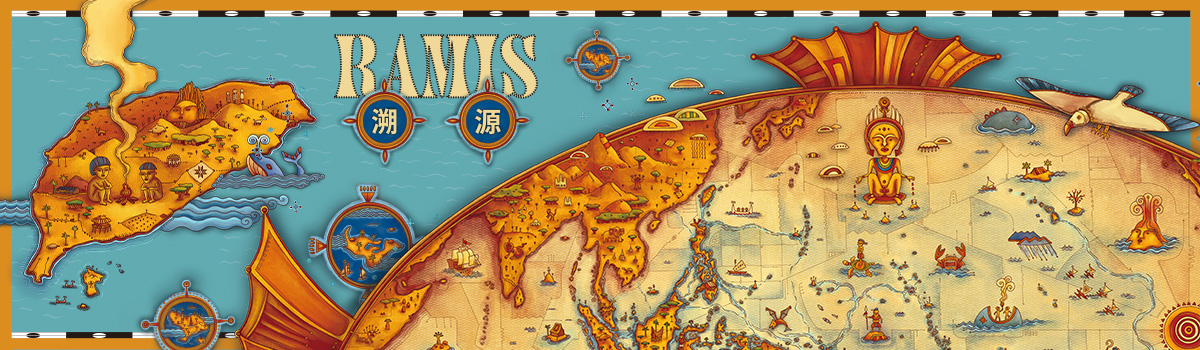

Taiwan is located on the Asia-Pacific Ocean, and on the world map, its landscape, temperature, humanities, art, etc. play an extremely important role. According to anthropologists, Taiwan’s indigenous peoples belong to the Austronesian language family, and have close ties with the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia and Oceania and other Austronesian peoples. The Austronesian peoples are the most widely distributed ethnic group in the world, with their distribution area extending from Madagascar Island in southeast Africa across the Indian Ocean to Easter Island in the Pacific Ocean. Taiwan is located at the northernmost end of the Austronesian distribution, and the southernmost end is New Zealand. In recent years, many Pacific island countries or Austronesian peoples have called Taiwan the mother island, meaning the centripetal force and sense of co-weaving of the Austronesian peoples towards Taiwan. Archaeologist Peter Bellwood and linguist Robert Blust both proposed the “Out of Taiwan” theory of the Austronesian language family. Later, Jared Diamond published a short article in Nature magazine titled “Taiwan’s gift to the world”, describing the importance of Taiwan’s indigenous peoples in the Austronesian language family, and pointing to Taiwan as the source (RamiS) of the Austronesian language family.

“RamiS” means “root” in ancient Austronesian languages, and there are many cognates of this word in the Austronesian languages, such as rami in Puyuma language, ramisi in Rukai and Kanakanavu languages, lamis in Bunun language, lamit in Amis and Sakizaya languages, and gamil in Atayal and Taroko languages. Language is a tool for human communication, and similar languages indicate that there must be similar cultural experiences. Based on the long-term analysis and research of linguists, it is proposed that Taiwan may be the origin of the Austronesian language family. Thousands of years ago, Austronesian languages, cultures and species spread from Taiwan to Southeast Asia and Oceania, passing on languages, cultures and stories on each island. The Austronesian peoples inspired each other’s life experiences, established common values of thinking, and reproduced from generation to generation under the harmonious coexistence of humans and nature. However, today affected by industrialization, capitalism and colonialism, human life and ecological environment are facing the edge of collapse. How should we live in the future? “Tracing back to the source” may be another way of thinking.

Following the path of dissemination of the Austronesian peoples, we can trace back to the

ancient cosmology. The myths and legends, music and dance, crafts, pantheism and tree-building genes that have been passed down for thousands of years by indigenous peoples are all sources. The language, ocean knowledge, land ethics and ecological philosophy inherited by the Austronesian peoples will also be answers to construct human future life. “RamiS” can bridge the gap between humans and species, science and nature. Under the ancient Austronesian language tracing back thinking, the existence and life wisdom of indigenous peoples are extremely important to be valued and advocated. To create a learning attitude that is spiritual and respectful of nature, we can move towards a future where all things coexist. Following the trace of tracing back to the source of the Austronesian peoples, in autumn 2023 at Taiwan Indigenous Peoples Cultural Park (TIPCP), we planned for first “Taiwan International Austronesian Art Triennial”, with two sub-themes proposed by two curators: “Becoming a Spiritual Person” and “Why We Are Us”, to present and discuss coexistence root proposition between “human” and “us”.

The plights of Indigenous people are being viewed with greater concern around the world, and correspondingly, so is Indigenous art. In recent years, Taiwanese Indigenous artists have been invited to various major international exhibitions, including Documenta, the Biennale of Sydney, the Asia Pacific Triennial, the Liverpool Biennial, and the Yokohama Triennale, to present their diverse, rich cultures and art. In addition, the global Indigenous art sector is actively working to connect and reveal the colonial mindset behind imperialism while exploring Indigenous people’s current struggles for survival. This involves such aspects as decolonization, identity, political borders, water resources, climate change, material resources, LGBTQ+ issues, healing, food, and much more. Behind this multifaceted proposition lies the core of Indigenous peoples’ ages-old spiritual cultures. In considering the relationship between humanity and the Earth, Austronesian people’s animist religions can give us some useful insight.

In modern times, people have tried to dominate the world and overcome nature, leading to frequent wars, epidemic outbreaks, and major changes to the ecology all over the globe. Meanwhile, nature’s consequential backlash has put human survival at serious risk. As humanity seems to be hurtling toward its demise, we may be able to learn from the ancient wisdom and experiences of Indigenous people. The name of this year’s event, RamiS: Tracing Origins is a reflection of the idea that we perhaps need to actively become spiritual to collaboratively think about the sustainability of humanity.

I had an animistic experience in the summer of 2000 when my family and I returned to our home village of Makotaay for an ilisin (harvest festival). The men’s vocals rang out loud and clear, their dancing feet at times tranquil, at times seeming to fly. When the mirecok (the final song/dance) came to an end, Lekal Makor, our kakitaan (community leader), who was in the middle of the circle, left in complete satisfaction. On the way home, he pointed to the right and said to me, “itira ira ko faki iso ato mama iso” (Your father and uncle are over there). As the two of them had already passed away, I was stunned, but I realized that is where Lekal meets with our ancestral spirits. The incident initiated my consciousness and belief in the animism of my people, the Pangcah . Besides the Ilisin, the misacepo’ (sea festival) held every May is another major event in our community. It is a time of supplication to Diwa Masiwsiw, the Pangcah god of the sea (one of the many Pangcah deities), for the success and safety of those who fish and gather resources from the ocean. Regarding his piece Messages from the Fish, artist Iyo Kacaw recalls that when a family member diving with him went missing once, his ancient wisdom of the ecology led him to follow the fish, and by doing so, he indeed found the person. As Hawaiian author Karin Amimoto Ingersoll has said, “Hawaiian ways of being-in-the-sea transcend the physical world to include the metaphysical, spiritual, and sensational, creating codes of grammar through seascape epistemology, which normalize an indigenous sense of knowing and being that travels.” 1 In Indigenous communities, hunters, the ocean, and other life forms have long been in a relationship in which they can feel each other, and the concept of animism exists in daily activities. So when the unknown is set to take place, this faith provides a sense of calm . 5,000 years ago, the Austronesian people group formed in Taiwan, from where it spread to islands in the Pacific and Indian oceans. Upon spreading even further, it has become the most extensively distributed people group in the world, with nearly 400 million members. These people were quite skilled seafarers in their use of the stars and understanding of currents and winds. For millennia, they crossed oceans and engaged in exchange, sharing the wealth of the sea. With the rise of industrialization, capitalism, and colonialism in recent times, the Austronesian culture has gradually declined, and human-induced climate change has directly impacted their homelands. Is humanity to continue on its path to destruction? Can we keep things from worsening? If so, how?

Most Austronesian people groups are traditionally animist, that is, they believe all things in the world (mountains, water, plants, animals, humans, etc.) have spirits, and they also believe their ancestors’ spirits live on after physical death. There is a tight bond among humans, nature, the ancestral spirits, and divinities, so Austronesian people worship nature and revere the ancestral spirits to maintain harmony among themselves and everything else. Taiwanese Indigenous writer Pasuya Poiconx believes that before Western religion came to Taiwanese Indigenous communities, animism was the core of Taiwanese Indigenous people’s religious beliefs. From the perspective of having to adapt to the environment to survive, the belief serves as a form of gratefulness to nature.2 Indigenous people’s animistic beliefs are manifested in their daily activities, such as hunting, gathering,farming, music, dance, weaving, pottery- making, and traveling, as is their reverence forall kinds of life regardless of species, race, or gender. In other words, Indigenous people, who strongly believe humans are a part of nature, have carried on the wisdom and harmonious coexistence with all things for millennia.

Why We Are Us I remember attending the 2016 Festival of Pacific Arts in Guam, with 27 participating island member nations. A young man from New Zealand’s Maori community introduced “us” from Taiwan when sharing his literature and poetry works, referring to Taiwan as the Mother Island for all of “us.” His words were met with enthusiastic applause from the audience. In that fleeting moment, I was awash with a profound sense of reassurance and affirmation; Taiwan was embraced as a member of the Austronesian linguistic community. For millions of years, Taiwan has been home to various indigenous groups residing in the mountains, plains, coasts, and islands. With a population of almost 600,000—nearing 3% of the total population—these mountain and coastal tribes are a treasure trove of rich, vibrant, and unique artistic and cultural assets. Like waves in the ocean, they have documented and passed down the practices of successive generations of art practitioners. Since the 1990s, Taiwan has seen a surge in social movements, such as the Indigenous Land Movement, appeals for survival, and the Name Rectification Movement. These movements have catalyzed a newfound ethnic self-awareness and anti-colonial consciousness among indigenous communities and propelled Taiwanese indigenous art into a new phase, profoundly influencing its creative lexicon. By engaging with currents in modern and contemporary art, indigenous artists have worked to elevate both the spaces for art exhibition and the arenas of spectatorship, highlighting the multifaceted and autonomous nature of their own cultural and artistic expressions. Through the integration of both tangible and intangible cultural assets, as well as traditional crafts, music, and dance, these artists are steadily carving out a unique identity for Taiwanese indigenous art.

Taiwan, often hailed as the Mother Island of the Austronesian language family, not only focuses on its own artistic and traditional cultural development but also aspires to deepen its affiliations and exchanges in arts and culture with other Pacific Austronesian nations, thereby shaping the future developmental trajectory of Taiwan’s cultural and artistic landscape. An indigenous tribal elder once said, “A qinaljan (which means “true tribe” in the Paiwan language) is a community interlinked under the norms of traditional and natural laws, a collective that venerates the sky and reveres the earth, sharing burdens and joys alike.” The “qinaljan” is a collective organized by “us,” a tapestry of individuals learning to support, appreciate, and share a common culture, a cosmology of concentric circles thatconnect human-to-human and human-to- nature dependencies. Within the “qinaljan,”tribal members establish their ontologies and epistemologies, perpetuating traditions and sustainable norms and beliefs. In Ways of Seeing, renowned British art critic John Berger stated, “Seeing comes before words,” which means we first gain knowledge of the world around us through sight, and then we employ language to articulate those experiences. This notion echoes the elder’s notion of “qinaljan.” Early Taiwanese indigenous tribes lived under strict social norms where “seeing” and “language” formed the matrix of their interdependent relationships with nature. Known as “gaga” in Atayal, “rikec” in Amis, and “kakudan” or “papaqaljayan” in Paiwan, these terms refer to the regulations of life, encapsulating a cosmology and ecological philosophy born from “seeing” the created world and then weaving it into laws of “language.” This philosophy is then visually rendered and graphically elaborated through skilled hands, or “lima,” in life’s manifold experiences.

Examining both the past and present of colonialism, we—the Austronesian “us”—all bear the indelible marks of colonialization. We are bound by collective traumas and confronted with common challenges and shared solutions. Between the islands and the sea, we are in mutual pursuit of our nomadic pathways and the symbolic seeds of sustainable growth. Through the intricate textures woven by “lima,” we embark on a shared odyssey to decipher the fluid consciousness and connective networks encapsulated in points, lines, and planes. This collective endeavor allows us to offer each other unique vantage points that lend the Austronesian collective a nuanced sense of memory and symbiotic significance. Concurrently, within the tapestry of our lived experiences, we are collectively mining for the transformative energy needed to mend the scars of historical traumas, because since the 17th century, Austronesian communities have largely been subjected to the incursions of external colonial forces. The so-called “modern civilization,” ushered in by colonial powers, has usurped our linguistic, cultural, architectural, and traditional autonomies, consequently altering our knowledge system, which is grounded in the land and eco-symbiotic ethics. Even our educational paradigms have alienated us from the very marrow of our cultural heritage. Moving forward, we are compelled to master the art of mending and re- deconstructing our languages and humanistic arts. We must also establish collective pacts to reimagine and reshape our spiritual landscapes, harmonizing them once more with the land, the sea, and the imperatives of ecological justice.

The paper mulberry tree, commonly seen in Taiwan, is not just significant to Austronesian culture but it is also a keystone species in botany, anthropology, and history for understanding the Austronesian world. Austronesian people have long used the paper mulberry to craft practical bark cloth by pounding its bark, a symbol with significant cultural meaning in the Oceanic archipelago and a material culture highly representative of the Austronesian community. In their collaborative installation work Ocean of Island Boats, artists Tuwak Tuyaw and Chen Shu- yen (Taiwan) use multiple materials like bark,fiber, driftwoods and huaz to create designs resembling boats, fruit, and seeds, suspended outdoors in the exhibition space. These designs symbolize fluidity, navigation, and dissemination, echoing the “Out of Taiwan Hypothesis” about Austronesian origins, and corresponding with the history of Austronesian migration. Taiwan has always been a vibrant island, rich in diverse qualities in geography, species, and culture. Facing the Pacific Ocean, we are not alone on this island in the sea; we exist in a web of interrelations, each thread imbuing our unique characteristics and vitality. Another outdoor artwork is The Form of Ancestors by artist Kulele Ruladen (Taiwan). He takes the ancient energy of fire as his creative concept, converting this ancient energy into a modern electrical force that continues to drive the progress of the era, depicting how the wisdom and beliefs of our ancestors can manifest in a modern form through technology. Ancestral wisdom is an ancient form of energy, and it remains etched within us and within the vistas where we focus our gaze.

Its spirit traverses the corridors of time and space, ceaselessly nurturing and protecting us. Kulele Ruladen uses this mechanically powered installation to explore the bridge of communication between humans and spirits. Even though we have undergone different evolutions and migrations through time, we believe that ancestral spirits are always present. Invoking the symbolism of the “eagle” as one such form, the artist invites these spirits to engage with this exhibition, allowing “us” to trace our shared origins. Within the interior of the Indigenous Lifestyle Exhibition House, the journey into the circular room begins from the lobby. Viewers are greeted by artist I Made Sukariawan’s (Indonesia) large-scale work Barong. The Barong is a mythical mask, a guardian of tribal villages, and a composite of various animals. Entering the exhibition space through the mouth of the Barong lion, installed in front of the visitors is the Starting Point exemplifying the Contemporary Indonesian Balinese style. This symbolizes the act of opening and entering of the artistic realm of the Pulima (artisan) family. Inside this bamboo-arched chamber that mimics the belly of an animal, I Made Sukariawan’s wooden Barong sculptural series—the Elephant series, the Miracle series - Turn Around, and Oh Water?—allegorically speaks to how artisan families are caught between the functional and cultural values of tradition and modernity, encapsulating the historical circumstances and challenges they have faced, and simultaneously imprints the functionality and value of Pulima in the Austronesian artistic thought.

Further into the circular space, visitors are greeted by the artwork Dalan (Road) by artist Milay Mavaliw (Taiwan). Drawing inspiration from her cultural context and point of origin, this installation and painting features intertwined, woven hemp-colored materials that are suspended from above and cascade down to scatter across the floor, connecting mounds of earth and stones scattered on the surface. This visual metaphor establishes connections between islands, symbolizing both the source of water and waterfalls and the millennia-long historical and existential ties of the Austronesian people. Complementing the suspended artwork, murals adorn the adjacent walls—interlocking gazes of ancestors and our encounters with our islands, oceans, sun, and moon. Young Bunun artist Ali Istanda (Taiwan) brings her unique style and composition to her print work After the Flood, There Are Islands.

Through a fusion of literature and artistic expression of mythological tales, the work explores human connections with islands, oceanic environments, and interpersonal relationships from her own sense of identification with her culture. After the great flood, islands form, and people disperse. Some remain at their point of origin, while others drift away to other places with the water. Different paths are chosen, and new lives have been built. Our journey of flow, though different, bear a semblance of similarity. If our respective islands are to be found after the flood, then let us fully evolve into our individual selves, while remembering the experiences of “us”. Adding to the portfolio of printmaking is 13 Months, where the artist outlines her perception of ecology through the lens of traditional calendrical culture, living in sync with the Bunun people’s lunar and mountain- oriented timekeeping amidst the perennial cycle of seasons, breaking free from the confines of time within each bustling month, and a unique 13th month quietly accrues, setting itself apart as distinctly its own. The artwork of Yuma Taru, titled Sea, Rise and River . Flow, reflects recent studies and observations on issues shared by Austronesian communities, particularly the material culture of mollusks found in marine and river environments, investigating their intricate narratives that interlace with the Austronesian peoples. The artist’s ambitious 50-year creative plan, centered on weaving and chanting, thoroughly exploring the cultural and artistic essence within Austronesian vocabulary.

Immersed in the delicacy and sustainability of maternal arts and culture, the artist combines diverse and eco-friendly materials such as ramie threads, wool yarn, stainless steel enamel-coated wire, metallic threads, wooden boards, etc., in her installation art. This presentation reflects the artists keen observation of the ever-changing nature, resonating amidst weaving and entwining, conveying profound awe and lament for the mountainous and aquatic regions—the origins of life—manifesting in an artwork of inner thoughts and expressions. The exhibition space alludes to the beachside, featuring the work of Tao artist Sya man Misrako (Taiwan), who was born on Orchid Island. In front of the beach, numerous small wooden canoes are suspended, and boats from Pacific nations like the Marshall Islands and Solomon Islands are placed upon the sand. The arrangement evokes how Austronesian language family acquire life and cultural significance from the sea, expanding the maritime routes of Austronesian peoples. Beyond the display of boats, a corner of the wall projects images of open-sea navigation accompanied by the sound of crashing waves. This captures ongoing discussions about contemporary challenges faced by Austronesian communities: youth migration and disorientation, the erosion of traditional crafts, boat-building techniques, language, and culture. It serves as a reflection and advocacy captured in the term Drifting Islands, the title of a work by Sya man Misrako. Totems record ancient stories passed down through generations. Pulimas narrate lives with land and nature through their carving. They also reveal a tangible ideological realm through their art. Taiwanese artist Ljailjai Tult (Shen Wanshun) installed seven colossal wooden figures next to the traditional slate house, an existing feature of the exhibition. Arranged in a linear progression from rudimentary carvings to finely detailed, from monochrome to colorful, these figures gaze intently forward, in a unified direction. Their gaze points towards the origins of the Austronesian language family—the dwelling place of ancestral spirits, the starting point for human life, language, culture, and mythologies.

This place is also the subject of Ljailjai Tult’s work i tjailikuz (Our Future Tense). Mythology often serves as an eternal narrative or symbol of immutable human truth, usually situated within the realm of aesthetics. Artist Siyat Moses (Taiwan) explores this in her works Ririh: Past and Present and Ririh: I Can Draw a Circle. Drawing inspiration from the Seediq Tribe’s folklore of the “Sisin” bird (Grey-cheeked fulvetta), Siyat employs the figure of the bird traversing seven circles as the central motif of her artwork. Created through silk printing interwoven with textile and mixed media, these seven circles symbolize that though the Sisin bird has evolved over generations, its spiritual significance from tradition to modernity remains intertwined and relevant in the aesthetic and cultural existence of “us.” The collaborative artwork of young artists Ljaljeqelan Patadalj and Sudipau Tjaruzaljum (Taiwan) employ video and hand-weaving to explore the topics of migration of “return”, seeking pathways for reclaiming individual agency and the cultural self-awareness and identity of the new generation, at the same time redefining the essential relationships between human existence and our environmental sphere. In their work pacacada(distance), the “ocean” serves as a cultural bridge of Austronesian language family, while human bodies navigate the migratory routes. These geographical features—mountains, rivers, and sea— intertwine and engage in dialogue amid history, and in a certain spacetime, their existence is not merely linear but an extension of curves. In the A Voice series, traditional shell ginger weaving techniques are employed by the artist to question the sense of distance in human shaping through facial recognition systems, using the presentation of the artwork to voice a “dialogue.” Whether in the natural landscapes of their native lands or in bustling urban cities, the artist conveys a longing: to emerge from the labyrinth of existential uncertainties and to articulate a clear sense of identity and belonging through their artworks, grappling with the ambiguities of “resemblance and difference”. In the final space of the indoor gallery, which also serves as the exhibition’s exit, Taiwanese artist Anguc Makaunamun’s Memory Tablet series offers a reinterpretation of contemporary urban indigenous identities, adrift between their homeland and urban settings in the face of changing colonial history. The Among Beast Heads series starts with his childhood experiences with the supernatural.

By rearranging human, animal, and plant features, new totemic symbols are conceived, establishing new connections between human beings and the natural environment. These works attempt to build a collective space for “us” to worship and a lifestyle rooted in pantheistic faith, paving the way for a ceremonial approach to life that gazes upon a whole new future . Stepping out of the indoor exhibition space, another installation situated in the outdoor Performance Hall (kakataliduan) greets the visitor. Malaysian artist Chee Wai Loong’s piece, Homesick, positions the ocean as its central motif. Using the lighthouse in the middle of the ocean as a symbolic image, the artist situates a traditional Malay stage house in the center of the sea, its rooftop adorned by a cultural Malaysian kite. Through the drifting forms, the sound waves, and the play of light and shadow of the work, the artist hopes to facilitate a destined reunion between the Austronesian ancestors and the “us” of today. It also aims to provide those who are abroad with a beacon to find their way back to the home they long for. Thousands of years ago, the Austronesian people spread from Taiwan across the ocean to the islands of Southeast Asia; the sea carried language, culture, and seeds to other islands worldwide; in essence, connecting us all. This maritime connection transcends distance, time, and space, uniting the hearts of “us” in a single, collective experience. The positioning of the work allows a clear view of the Ailiao River below, a significant local waterway that flows into the sea in the west, resonating with the artist’s work: trace back its origins, and one may find their true home within. The curatorial concept of Why We Are Us centers around life rituals, mythologies, linguistic cultures, ornamental patterns, ecological philosophies, and migration stories experienced by the artists. The exhibition aims to construct a discursive space in which Austronesian artists can engage, recognizing the collective threads and historical memories that bind them. The visual art created by “lima” serves as a connective thread, offering a lens through which to reflect on human behavior in the face of contemporary intellectual currents. For ages, the “lima” among “us,” the Austronesian people, has been narrating the stories we’ve heard and the paths we’ve walked. Through the life experiences of the artists, critical issues that are collectively faced by “us” in modern times are elaborated. Simultaneously, the creation of art establishes a shared spiritual landscape for admiration and mutual understanding, equipping “us” with the skills and aesthetics needed to navigate existing predicaments.

The practice of artistic creation serves as an “aesthetic emancipation,” conveying the relationship and interpretation between humans and with the natural world. This is also the sublime value of art and action, inspiring people to feel the inner workings of their self and the dawning light of the future. Our Austronesian “Lima Aesthetics” must connect with the traditional ethos of our people and necessitate a relationship with the painful memories of ecological catastrophes that have befallen our islands, lands, rivers, and oceans. These aesthetics also demand a dialogue with our own cosmologies and existential rights, the axioms of our ancestral wisdom. Only through such a retracing of roots can this endeavor become both lucid and everlasting.